During the last twenty years, I have served as a critical incident stress debriefer for emergency service workers and clergy in disaster zones, and I have seen firsthand how those experiences change physical, social, emotional and spiritual landscapes dramatically. I am not an expert in disaster response and recovery, but I have studied the dynamics inherent in disaster situations and served with first responders, mental health professionals, social scientists, and people who have lived through disasters.

Here are some lessons I have learned:

All disasters are local. A strong tornado can hit two communities thousands of miles apart on the same day. While the destructive force of the tornado can be quantified, its impact will be different in each community. Likewise, each diocese and congregation will be affected differently by the Covid-19 pandemic and will react differently depending on its specific contexts.

All disasters make both individual and collective impact. Laypeople, clergy and bishops in every diocese are being impacted individually by the pandemic, and our communities of faith are being impacted collectively. Personal impact reveals itself in grief and stress reactions, and there is nothing abnormal about this. Grief and stress are normal reactions of normal people to abnormal events.

Our patterns of daily functioning in congregations and dioceses are already severely disrupted by shelter-in-place orders, illness and death, loss of access to buildings, and diminished revenues and resources. Our systems are also being affected by the grief and stress of the individuals in them.

In a disaster, spiritual questions always surface, even for people who are not religious. Some people are angry or feel distanced from God. They ask, “How could God let this happen?” Some people turn to God for comfort and strength. Some focus on issues of justice and the moral imperatives of the gospel, asking how best to serve as agents of God’s love and mercy. The search for meaning and hope is always intensified during times of disaster.

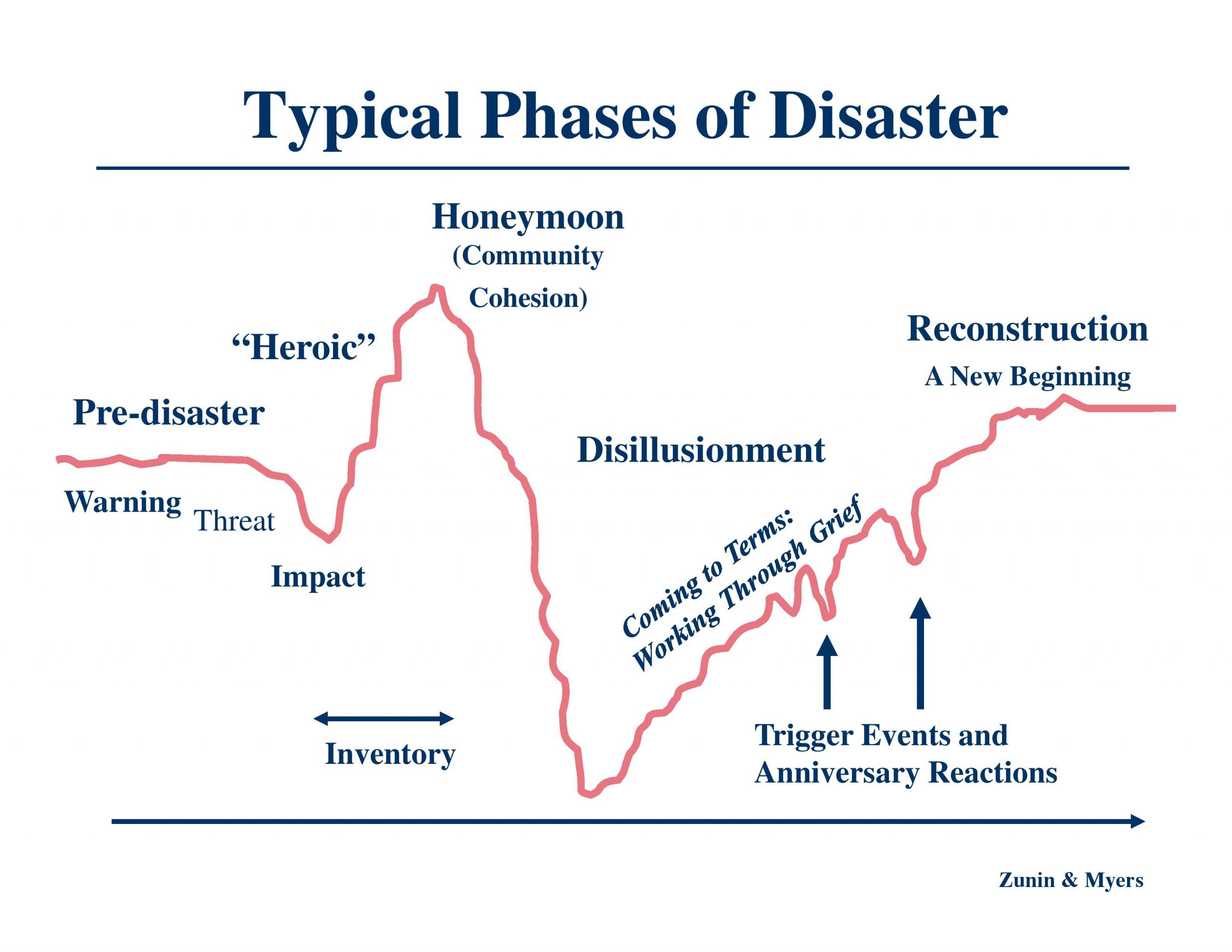

In light of these dynamics, I find it helpful to think about the phases of disasters. Diane Meyers and Leonard Zunin, medical experts in trauma and loss, developed a widely used conceptual framework of disaster response and recovery. Their chart (below) describes the pattern of individual and community activities and reactions. The phases are relatively predictable, but they may overlap, and movement along the timeline is not strictly linear. As you would expect, there are variations among individuals and communities.

Threat

The threat phase is before the disaster occurs, and there can be a variety of reactions. Some prepare and warn others even though their warnings may fall on deaf ears. Others are blissfully unaware or in denial that a real threat exists – “That couldn’t happen here.”

Warning

The warning phase occurs when it is highly likely that a disaster will occur. A “tornado watch” means that conditions are right for a tornado. A “tornado warning” means that a tornado has been spotted and people need to take cover. People often respond to a warning with initial disbelief and reluctance to act. People sometimes normalize or psychologically downgrade a warning to make the situation less threatening or dangerous. A frequently cited example in disaster literature tells of people in a small town hearing the roar of an oncoming tornado and mistaking it for a freight train, even though the town had no train tracks.

Impact

Impact can last a few minutes or, in the case of war or famine or drought, can last years. We are living now through the pandemic’s impact, and the time, duration, and intensity of the impact will be different across our church.

Heroic

This phase happens during and immediately after impact, as people use enormous energy and ingenuity to save their own and others’ lives and properties. Today, our health professionals are truly heroic in their response to the coronavirus.

Honeymoon (Community Celebration)

Once danger is no longer imminent, survivors may be elated and happy just to be alive.

People may have a strong sense of having shared an intense experience and lived through it. There are generally high expectations that there will be great assistance from official and government agencies. This phase doesn’t last, nor does its accompanying belief that someone from the outside will come to the rescue and make it like it was before.

Disillusionment

In this phase, reality hits home. The extent of loss becomes apparent, and people can assess whether or not necessary resources arrived in time. Especially if there were delays, failures, or unfulfilled hopes regarding aid and assistance, people may experience strong feelings of disappointment, anger, resentment, and bitterness. During this phase, people tend to concentrate on rebuilding their own lives and solving their own problems. The feeling of shared community is lost.

The great danger of this phase is that community cohesion and collaboration will decline as old and new conflicts arise over who to blame, who gets resources, who is in and who is out, who has power and influence, and whose priorities for rebuilding and recovery should prevail.

We cannot afford to get stuck in this place because it will suck the life right out of our leaders and communities.

Coming to Terms with a New Reality & Working through Grief

In the coming months and years, we will need to recognize and work through the grief that accompanies spiritual and emotional loss. Some people will lose loved ones, homes, and jobs. For others, hopes, dreams, and assumptions about life may be shattered. Still others will get over it quickly and move on. All of these post-disaster stress and grief reactions are normal reactions to an abnormal situation.

Reconstruction – A New Beginning

FEMA’s definition of long-term recovery refers to the “need to re-establish a healthy, functioning community that will sustain itself over time.” We will all be engaged in long-term recovery from this pandemic for months and years to come. We will need one another, in ways we cannot imagine now, to rebuild.