Good evening! Thank you so much, Fred and Bayani, for inviting me to join you for this wonderful Episcopal Asiamerica Ministries Consultation. And thanks to all of you who have included me in your conference sessions, workshops, and social time. This is the third time I’ve been fortunate enough to be with you at this consultation, and I always look forward to my time with you.

I’m especially pleased to have been with you for the commissioning of the ANDREWS mentors and to have spent time with so many of you who are new mentors. In committing yourselves to fostering and strengthening clergy and lay Asiamerican and Pacific Islander leaders, you have made a tangible commitment to revitalizing congregations and creating new ministries for the 21st century church. I am grateful for your work among us.

On Thursday, when we commissioned the ANDREWS mentors, we remembered the 70 elders gathered by Moses to receive the spirit of the Lord. Now, as we prepare to return home tomorrow, it’s important to remember—ANDREWS mentors and all of us gathered here—that the reason Moses took the step of gathering 70 elders is that the people of Israel were whining. A lot.

It’s all there in Numbers, which is one of the appointed readings for today. You might have heard it in the local congregation where you attended church this morning.

The Israelites were wandering in the wilderness, and they were hangry. You know hangry—it’s when being hungry makes you angry. If you’re unfamiliar with this state, find a teenager and hang out with him for a day or two.

“If only we had meat to eat!” the Israelites whined. They should have been here tonight—there’s definitely no room for whining at this banquet.

And then they did what people who are tired and scared and facing an unknown future do. They got nostalgic about the past.

“We remember the fish we used to eat in Egypt for nothing, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic,” they said. They forgot, apparently, that when they were in Egypt, they were enslaved.

And then, they did the other thing that people who are tired and scared and facing an unknown future do. They complained about what they did have.

“…Now our strength is dried up,” they said. “And there is nothing at all but this manna to look at.” In other words, there is nothing but what God has given us, and it is not enough.

These responses—getting nostalgic about the past and complaining about what God is providing right now—will not be new to you if you’ve spent much time as a church leader here in the 21st century. Too often, we Episcopalians—let’s be honest, we white Episcopalians—behave like the Israelites when we think about the past: “Remember the 1950s, when our Sunday Schools and our collection plates were full?” we say, without bothering to recall that the good old days of the institutional church were only good for some people, and that the reasons they were so good for a few are inextricably bound up with the institutional racism, sexism and classism that still infect our church and our world today.

And too often, like the Israelites, we Episcopalians also complain about what God has set down right before us: “We don’t have enough people in the pews,” we say, ignoring the incredible richness of the people we do have—people who are motivated to come to church not by conformity or societal standards, but by love of Jesus and belief in the power of the Gospel to change lives and bring about justice and peace. “The world doesn’t pay attention to the institutional church anymore,” we complain, conveniently ignoring the fact that the church with which powers and principalities was enamored was far too often the church that chose the ways of the world over the ways of Jesus.

But when I spend time here at EAM, I don’t hear that whining and complaining. This weekend, I haven’t heard nostalgia and wistful longing for an imagined past. Here I experience Anglican traditions formed not by the glorification of all things English, but formed in spite of the violence of imperialism and cultural hegemony. Here I find Christians whose identity is formed not by loyalty to the church of power and white privilege, but as a means to resist the injustice perpetrated by white American leaders, many of them Episcopalians, who enforced the anti-Chinese Exclusion Act of 1842, the demeaning discrimination of Angel Island, the harsh working conditions and poverty of immigrant workers, and the military colonialism that devastated so many Asian countries and communities. And here I experience Christian community that is today determined to resist the racist, xenophobic, anti-immigrant hatred that currently holds sway in the White House and in the United States Congress.

What I’ve seen and experienced here—in the commissioning of the ANDREWS and in so many conference sessions and conversations—is your clear-eyed understanding of the church’s past coupled with your eagerness for the church of today and tomorrow. You are exploring new methods of cultivating the next generations of leaders, new models for creating Christian community with Jesus at the center, and new ways of raising the church’s voice on critical issues of sovereignty, peacemaking on the Korean peninsula, environmental justice and racial reconciliation.

As I look toward my final triennium as president of the House of Deputies, I am convinced—convicted, as the old-time evangelists would say—that leaders like you here at EAM are the leaders who will lead our beloved church out of the wilderness in which we currently find ourselves. Because, make no mistake, we Episcopalians are wandering, and even when we know that the Promised Land awaits us, we are too often tempted to think of, or even to long for, the land that we have left—to get hangry and nostalgic and to sit right down here in the wilderness and wait to die.

But, as Anne Lamott says, God loves us exactly the way we are… and loves us too much to let us stay that way. God has given us leaders like you to follow, and God has given us manna for the journey and gatherings like this to give us a vision of the Beloved Community. Some of us—I’m looking at you, fellow Baby Boomers—may only see from a distance the full realization of God’s promise for the future of the Episcopal Church. And others of you will be the prophets and the preachers and the scribes who will not just save the church from institutional death, but who will usher in the resurrection to which we are called by God in our cities and communities and congregations in all the countries and cultures of the Episcopal Church.

Thank you, and God bless you tonight and always.

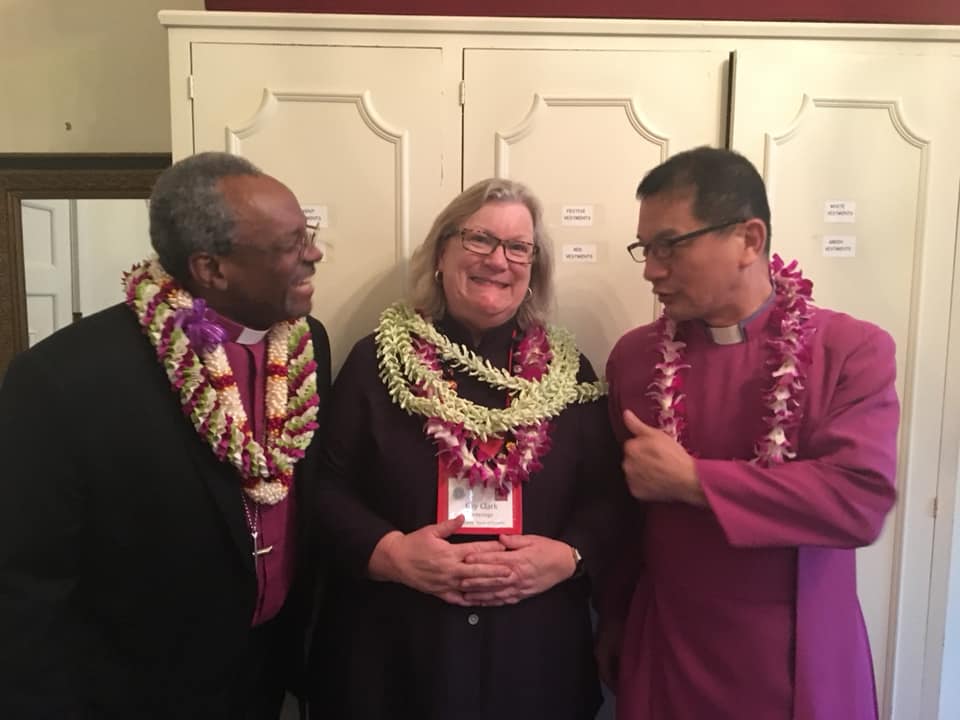

photo courtesy of the Rev. Canon Stephanie Spellers: Presiding Bishop Curry and President Jennings with the Most Rev. Moses Nag Jun Yoo, primate of the Anglican Church of Korea