President Jennings gave these opening remarks to an online meeting of Executive Council on January 22:

Hello, and welcome to this online meeting of Executive Council. We’re beginning to get good at meeting this way!

I’m grateful for this technology that allows our work to continue, but just because it has become routine, I don’t want to minimize the strain that it places on many of us and the staff who support our work. Thank you for your continuing perseverance in the face of Zoom fatigue, barking dogs, children home from school, glitchy home wifi, and the endless challenges of the mute button, not to mention economic uncertainty, spiraling COVID infection rates, and an existential crisis in the democracy of the United States. We see you, and we are grateful.

I want to spend my time today reflecting with you on what I believe our church is called to do about the forces that precipitated the crisis at the U.S. Capitol on January 6. But first, because there has been precious little to celebrate in recent months, I want to note some good news:

On Wednesday afternoon, just hours after his inauguration, President Biden issued an executive order fully implementing the Supreme Court’s June 2020 decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, which held that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 bars employment discrimination against LGBTQ people. In 2019, the Presiding Bishop and I had the honor of being the lead signers of a friend of the court brief filed with the Supreme Court in the Bostock case. In that brief, we joined more than 720 interfaith clergy and faith leaders in declaring that our religious beliefs compel us to support equal protection under the law for LGBTQ people. Our position, as with all of the public policy positions of the Episcopal Church, was based on the actions of General Convention—in this case, on multiple resolutions dating as far back as 1976.

Although the Supreme Court decision is more than six months old, the previous administration had not implemented it, and so yesterday’s executive order marks the first time that LGBTQ people have been assured of the legal protections the court had ordered. This is an enormous victory, and only because it came on such a momentous day has it not been given much attention.

People sometimes ask me about the point of General Convention resolutions on matters of public policy, and even question whether they make any difference. Yesterday, we saw the work and witness of many General Conventions culminate as a longstanding wrong was righted. This week, the Episcopal Church’s witness made a difference in moving the United States closer to justice for all of God’s children, and for that I give great thanks.

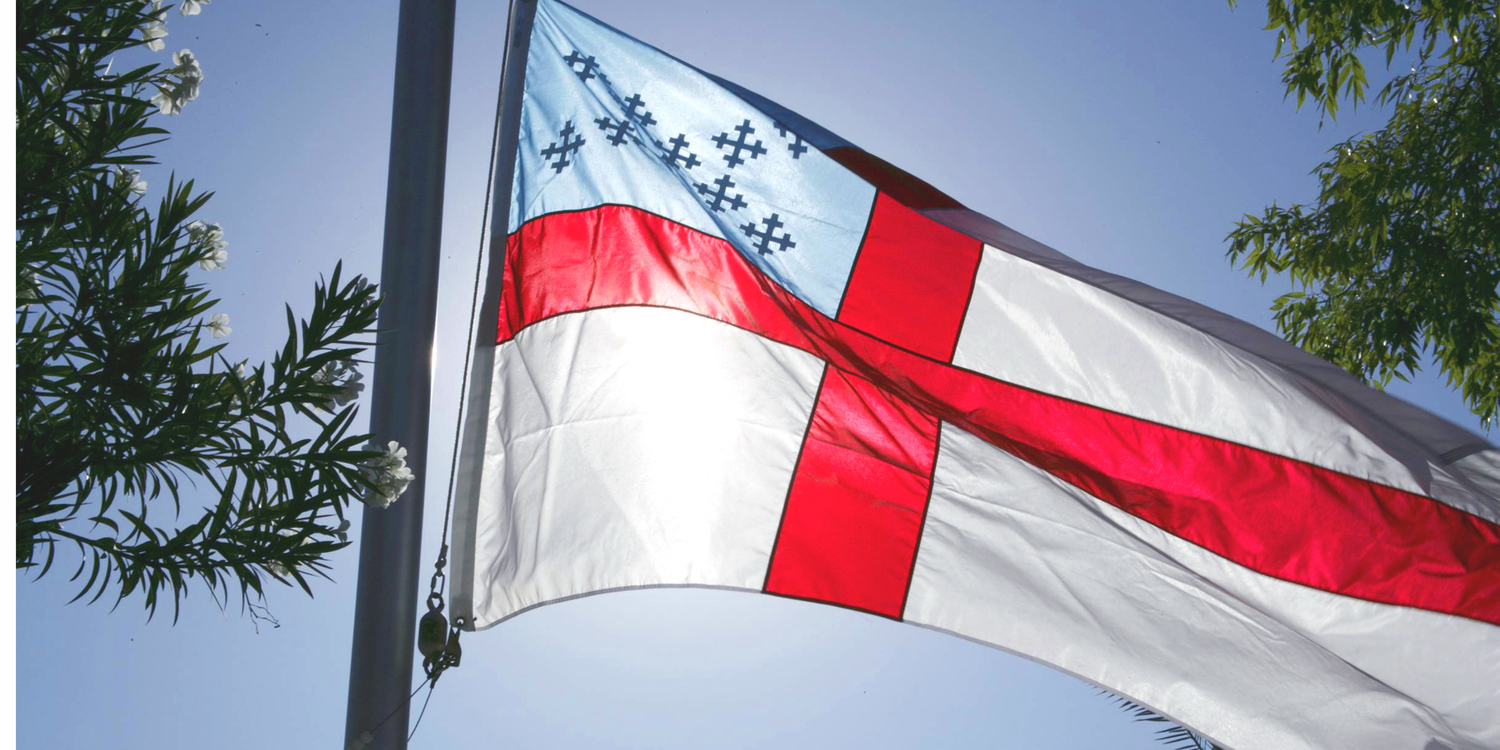

Now, unfortunately, not all of Christianity’s recent airtime has been that good. You have probably seen, as I have, the coverage detailing how white Christian nationalism fueled the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6. Signs, banners and flags carried by the rioters declared allegiance to Jesus and the former president, sometimes conflating them, and pledged fealty to God, guns, and America. One group styled itself after Joshua fighting the Battle of Jericho, marching to make “the walls of corruption crumble.” Others described visions from God endorsing their efforts to overturn the results of the presidential election or claimed that their efforts to save America from “tyranny” are inspired by God.

The stories, signs and symbols of our faith are being put to violent use by people who want to establish a nation in which power and privilege is held exclusively by white Christians. This isn’t simply a set of policy disagreements between liberals and conservatives, between people who want elected officials to enact laws based on one set of values instead of another. It is domestic terrorism. As author Katherine Stewart said in an interview with Sojourners last March:

…Christian nationalism does not believe in modern, pluralistic democracy. Its aim is to create a new type of order, one in which Christian nationalist leaders, along with members of certain approved religions and their political allies will enjoy positions of exceptional privilege in politics, law, and society. So, this is a political movement and its goal is ultimately power. It doesn’t seek to add another voice to America’s pluralistic democracy, but rather to place our foundational democratic principles and institutions with a state grounded in a particular version of religion, and what some adherents call a biblical world view.

In these hard days, when our country needs so badly to heal, it is tempting—for me, at least—to look the other way when we encounter Christian nationalists. We’re not that kind of Christians, we think. We want to believe that if we just talk across our differences or build relationships with people on the other side of the political divide, we can put this terrible nightmare behind us. We hope and pray that it’s over now because the former president is out of office and off of Twitter.

But the use of Christianity to advance white supremacist extremism did not begin in 2016, and it did not end at noon on Wednesday. This violent and exclusionary movement is on the rise in the United States, and those of us who believe that God is calling us toward a very different vision, toward the Beloved Community, have a special responsibility to stand against it. If we will not tell the world that it is not Christianity, then who will?

Last October, the Office of Government Relations (OGR) provided us with a white paper about ways that our church could consider becoming involved in deradicalization efforts that seek to reach those who have joined extremist groups and those who are tempted by them. Other Anglican Communion provinces have taken on this work, so there are models to follow and partners to consult. Here’s a passage from the OGR paper:

The Episcopal Church has the opportunity to respond to this threat by offering an “off-ramp” for those who have joined extremism groups, expanding the possibility of reconciliation and forgiveness. The Church can prevent those who are on the brink of joining radical extremist groups from doing so, inoculating young people from succumbing to these ideologies. Many at-risk people still have community connections through churches, whether through friends, families, or community members. With programming in place, clergy and church leaders who are trained in this kind of outreach could help pull young people back into communities and churches.

We didn’t give the need for deradicalization work serious attention in October. I suspect that some of us thought that it was an overreaction, or that it might be divisive to suggest that people with different political ideas from ours are dangerous, or that things would calm down after the election. And certainly, I do not mean to suggest that everyone who votes the opposite ticket from mine are thereby enemies of democracy or dangerous terrorists. There have been times in the past when my husband and I have cancelled each other’s votes, and we have been married for 44 years. I know with certainty that he is not an extremist; I hope he would say the same about me—at least on most days.

But this issue looks different now, doesn’t it? We’ve seen with our own horrified eyes what Christian nationalism can do to the Capitol, to the Congress, to the country. We know that sickening feeling of seeing the symbols and signs we hold so dear used to justify terror. We’ve seen our capital city occupied by thousands of troops because of credible threats of violence against our government and feared for the lives of our elected officials.

As Christian leaders who understand that Jesus calls us to live in harmony with all of God’s children, I think we need to look again at how we can be agents of peace through the work of deradicalizing those who distort our faith in deadly, destructive ways. I understand that the Joint Standing Committee on Mission Within The Episcopal Church began this conversation at our last meeting, and I hope they will bring a resolution to the floor for us to consider at this meeting so that we can begin to take this idea seriously.

Thank you, as always, for your work on behalf of our beloved church and the communities we serve.