Eternal and ever-gracious God, you blessed your servant Thurgood with exceptional grace and courage to discern and speak the truth: Grant that, following his example, we may know you and recognize that we are all your children, brothers and sisters of Jesus Christ, who teaches us to love one another; and who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever.

Today, May 17, in the Calendar of the Episcopal Church, we commemorate Thurgood Marshall, who served as a deputy to the 61st General Convention in 1964. Born in Baltimore in 1908, Marshall had an exceptional career as a civil rights attorney and was appointed Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1967. He retired from the Court in 1991 and died January 24, 1993. The church chose May 17 as his day to also commemorate the unanimous ruling of the U. S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, released on that date in 1954.

Beyond ruling that racially separate public schools were inherently unequal, the Court not only overruled the legal concept of separate but equal, but its action was also a spark for the modern civil rights movement. Over the next 14 years African Americans and their allies would struggle to end all aspects of legal segregation.

By 1965, the central strategy for the civil rights movement was to restore to all black citizens the right to vote. This right, guaranteed specifically to them in the Fifteenth Amendment, had been denied to virtually all black Americans in the South since the end of Reconstruction.

Early that year the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) invited Martin Luther King to Selma, Alabama, to join and invigorate their voting rights work there. The Selma to Montgomery marches began on March 7 with a violent attack on the marchers by Alabama state troopers seen on television news by Americans throughout the country, including President Lyndon Johnson. Johnson filed the Voting Rights Act ten days later. Meanwhile, King and SNCC called on Americans to join and complete the march from Selma to Montgomery on March 25th. Among the hundreds of Episcopalians who came responding to a call from the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity (ESCRU) were Judy Upham and Jonathan Daniels, students at what is now Episcopal Divinity School.

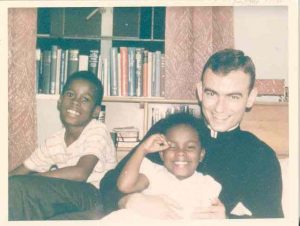

Daniels completed the march and returned to work that summer in Alabama. He was arrested in a demonstration and on August 20, 1965, and after being released from jail, was murdered protecting seventeen-year-old, Ruby Sales, from a threatening, armed, deputy sheriff. The Voting Rights Act had passed Congress and was signed by Johnson on August 6.

Courtesy of the Archives of The Episcopal Church

O God of justice and compassion, you put down the proud and mighty from their place, and lift up the poor and the afflicted: We give you thanks for your faithful witness. Jonathan Myrick Daniels, who, in the midst of injustice and violence, risked and gave his life for another; and we pray that we, following his example, may make no peace with oppression; through Jesus Christ the just one, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever.

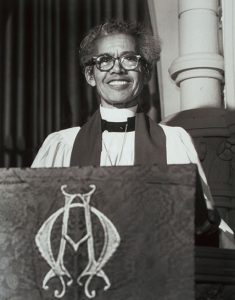

Daniels was murdered in Lowndes County, where more than 80 percent of the residents were African Americans. Yet the jury that acquitted Tom Coleman, the man who shot him, was entirely white. State law and local practice made it all but certain that juries in Alabama would be composed entirely of white men, and on the heels of the verdict in Daniels’ case, a team of lawyers, including Pauli Murray, who later become the first African American woman ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church, prepared to challenge the law.

Murray had already played an important role in the civil rights movement. In 1950, she wrote States’ Laws on Race and Color, a critique of existing statutes that Marshall and lawyers for the NAACP drew on in shaping their arguments in Brown v. Board of Education and other important cases. Marshall referred to the book as “the bible” of the civil rights movement.

As a result of the work of Murray and others, a U. S. District Court in Alabama ruled in 1966 in White v. Crook a ruled that jury service was a right guaranteed to all citizens under the 14th amendment.

Liberating God, we thank you most heartily for the steadfast courage of your servant Pauli Murray, who fought

Courtesy of the Archives of the Episcopal Church/Potomac Commercial Photographers/Capitol Photo service

long and well: Unshackle us from bonds of prejudice and fear so that we show forth your reconciling love and true freedom, which you revealed through your Son our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

The enforcement of the Voting Rights Act has successfully opened and protected voting for the majority of African Americans and has extended these protections to other Americans who have been discriminated against, especially those whose first language is not English.

Congress has renewed the act four times, most recently in 2006. And the act has been challenged unsuccessfully in a series of cases, with one challenge, Shelby County v. Holder, presently pending a decision of the Supreme Court.

When St. Augustine’s Church in Washington DC proposed Thurgood Marshall for the Calendar, they wrote, “The Spirit working through this man gave him an intuitive sense of justice in which he saw all of life as sacred and all persons equal before God.”

That Spirit works through Episcopalians right now. And many Episcopalians have worked and are working with “an intuitive sense of justice.” President Gay Jennings and I have an idea that we need to remember and hold up Episcopalians like Marshall, Murray and Daniels and those influenced by their work and witness. This past April, Martin Luther King has been dead 45 years. We have lots of people who have not heard the stories of the civil rights era from those who were there.

Where were you in 1965? In the comments below, tell us, tell the Church, your story.