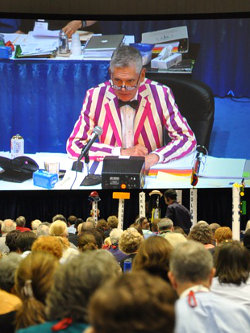

The Rev. Dr. Gregory Straub, executive officer and secretary of General Convention from 2006-2012

Remarks on the eve of being awarded a doctor of divinity honoris causa by Episcopal Divinity School, May 22, 2013

At the insistence of George Jessel, Groucho Marx joined the Friars Club.

He found club life not to his liking, so he sent a telegram to the club secretary resigning his membership. The telegram read, “I wouldn’t belong to a club that would have me as a member.”

Today I feel akin to Groucho.

When I convened the Honorary Degrees Committee for the Board of Trustees of this seminary, I didn’t qualify for an honorary degree. So, I want to begin by thanking my successor, Bob Steel, for lowering the standards and letting me in.

I told a friend that Dean Ragsdale had ‘phoned to say the board had voted to grant me an honorary degree. He asked, “What’s it for?”

Well, I didn’t know. It never dawned on me to ask the President and Dean why I might be given an honorary degree, which shows that humility would not be one of the reasons. I’m really looking forward to hearing the mandamus tomorrow and learning why EDS might give me an honorary degree.

Episcopal Divinity School has a proud tradition of conferring honorary degrees on recipients who have spent their lives promoting social justice. Unlike other seminaries EDS has not granted degrees pro forma to alumni

no matter how distinguished, unless they have moved church and/or society in a progressive direction or worked to bring relief to the poor and oppressed. I have done neither.

But let me propose to you what I hope to have done, and we’ll see if in any way it is consonant with what we hear at graduation tomorrow.

Social action, in church (or society), doesn’t happen in a vacuum. For unjust structures to be changed, the rules that govern church (or society) have to be changed. The church changes its rules in parish meetings and diocesan and general conventions. (Society changes its rules in board meetings and legislatures, but let me focus on the church.)

I’ve been privileged to have been present as a visitor to and as an alternate, deputy and, most recently, secretary, of the General Convention of the Episcopal Church. The General Convention is the body in the Episcopal Church that adopts the texts by which the church prays, that approves the commemorations that adorn the church’s calendar, that elects the officers who represent the church to itself and to the world and that adopts the laws and resolutions by which the church agrees to govern itself. While the General Convention is in session only for a matter of days every three years, its preparation and coordination require full-time effort between its meetings.

The General Convention can use its time productively, because a team of paid staffers and volunteers have worked to create the time and space for that to happen. The lights illumine, the air-conditioning cools, the microphones amplify, the cameras record and project, the voting machines count, the copiers reproduce. People have thought about every aspect of convention’s life and anticipated most every need. The number of circumstances that must be accommodated whilst planning for the General Convention grows with the church’s increasing sensitivity.

When I attended my first General Convention, we didn’t recycle paper; we didn’t offset our carbon footprint –no one then knew she or he had a carbon footprint, let alone thought about offsetting it; we didn’t have restrooms designated for transgender persons; we didn’t translate into languages other than Spanish; we didn’t have daily convention worship services, and the one Sunday service each convention we did have didn’t reflect the church’s diversity of membership or liturgical style.

These requisites accumulated over time, as the church became aware of, and responsive to, its full membership. The office I served in New York, the General Convention Office, keeps track of these and countless other details from convention to convention to assure convention-goers the time and space necessary for prayerful and thoughtful decision-making.

If you’ve been to a General Convention, you’ll know what strikes most visitors: that despite its size, it’s able to consider ample legislation in a considered way that respects the diverse views of its members. In 2003, when General Convention considered consent to the consecration of its first bishop-elect who acknowledged his homosexual orientation before election, the press commented repeatedly on the respectful tone of debate in the House of Deputies. I was a deputy and the assistant secretary for voting in the house at that Convention, and I was never prouder of our church for the way in which it conducted itself as at that convention.

I want to give you two examples of the way in which General Convention has moved in a progressive direction

in recent decades. When I attended my first General Convention in 1976, there were more Hispanic bishops and deputies than there are today, but most of them were members from overseas dioceses that have since become constituent parts of other self-governing provinces of the Anglican Communion. There were African American bishops and deputies. There were no women priests or bishops in the houses: there were no women priests or bishops period. There were no gay bishops or, at least, there were no publicly acknowledged gay bishops. And there were indigenous members of both houses. So, General Convention was already on its way to becoming what it is today.

What the church has come to understand of itself since 1976, however, is that its members (and those it seeks to attract as members) want to see somewhere within the church’s leadership persons like themselves. During the years I’ve known the convention the openly acknowledged comprehensiveness of the church has become increasingly manifest, because General Convention has changed the rules by which the church recruits and sustains its leadership. It’s now unremarkable that the presiding officers of the two houses of convention are women or that in the House of Deputies one woman followed another woman as president.

It’s now unremarkable that there are gay and lesbian bishops and lay and clerical deputies and transgender lay deputies, and it’s only a matter of time before there are transgender clerical deputies and bishops.

It’s unremarkable that four of the five senior members of the House of Deputies are African American. No one bats an eye at any of this today–in fact, we’re proud of it– but it’s a world away from the church of my first General Convention.

Two weeks ago I met a man, who told me he’d been arrested at General Convention in Denver in 2000 with Soul Force, protesting the church’s failure to provide benefits to the same-sex partners of ordained and lay employees. That failure is an example of how the church did not support its lesbian and gay employees, a failure that’s been addressed and corrected at the churchwide level and in many, but not all, dioceses, thanks to the operation of General Convention.

Not only do Episcopalians expect to see themselves reflected in the church’s lay and ordained leadership, they expect to see people like themselves held up to the church as examples of faithful life. We now believe it’s not just popes, kings and queens who merit inclusion in the church’s calendar of noteworthy lives, but persons in all ministries and in all walks of life. The church has gradually included in its calendar additional heroes, ones who have been cherished by parts of the church, now offered to the church-at-large, thanks to the operation of General Convention.

For the eight years I was executive officer of the General Convention I was steward of the church’s work in convention: coordinating the work of the committees and commissions that work between conventions and providing them resources to accomplish their work; advising them on how best to get their work before the church and, in some cases, enacted; and encouraging the hundreds of volunteers who serve on them. The work that is done by these bodies between conventions contributes to the programs and policies enacted by General Convention.

It has also been my pleasure to serve as secretary of the House of Deputies and of the General Convention. And when I say “pleasure,” that’s what I mean. While the work of convention is weighty and its decisions far-reaching, participating in General Convention should not be unrelieved earnestness or tedium. Serving God in God’s church should be an occasion for celebration and a source of joy.

I hope anyone will attest who attended any of the three General Conventions at which I served as secretary of the House of Deputies, that it looked as if I got a bang out of being secretary, and that’s only because I did get a bang out of it. I had fun keeping the machinery going, and it was my intention to communicate that sense of fun to the members of the house. What I hope I contributed to our common life was competence mediated by a light touch.

I’m hoping to hear at graduation tomorrow that it’s for my stewardship of the mechanisms by which the church has made social progress that EDS has chosen to honor this anomalous recipient.