“Rain is a blessing, and we know you have brought us a blessing,” Rita Ayeebo, the project manager at the Anglican Women’s Development Centre in Yelwoko, Ghana, told a group of nineteen Episcopal Relief & Development pilgrims waiting out a heavy shower under a roofed patio at the organization’s headquarters last July.

Bishop Jacob Ayeebo, Deputy William Miller and House of Deputies President Gay Clark Jennings on the pilgrimage bus

After several days visiting farms and villages in the heat and humidity of northern Ghana, the group of Episcopalians led by the Rev. Gay Clark Jennings, president of the House of Deputies of The Episcopal Church, welcomed the rain not only as relief from heat but as an answer to the prayers of local farmers whose crops are suffering from climate change and depleted soil. According to Episcopal Relief & Development, 90% of families in northern Ghana are dependent on farming to earn a living.

ADDRO (Anglican Diocesan Development and Relief Organisation), Episcopal Relief & Development’s partner in northern Ghana, works directly with farmers whose traditional farming practices no longer produce enough food to feed their families. Maize, soybeans, millet and yams are all common subsistence crops in the regions of Ghana where ADDRO is active, but its farming programs focus on maize and soybeans, crops that with improved management can result in significantly increased yields.

Yams growing in the garden of the bishop’s residence in Tamale.

Photo credit: Devon Anderson

“Our old farming methods are outdated,” said the Rt. Rev. Dr. Jacob Ayeebo, bishop of the Diocese of Tamale in the Anglican Church in Ghana and executive director of ADDRO. “The seed has changed, the soil is no longer as fertile, and our climate has changed.” The bishop’s knowledge of farming practices is not just theoretical; the yard of his official residence in Tamale is a large garden that grows yams, maize and tomatoes, among other crops.

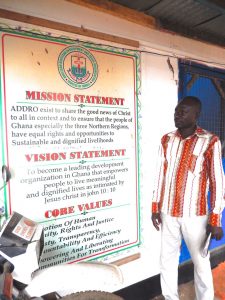

Emmanuel Tia Nabila at ADDRO’s offices in Bolgatanga

ADDRO’s farming programs use the principles of asset-based community development, a strategy for mitigating poverty that was adopted by The Episcopal Church in its most recent domestic poverty resolution at the 2012 General Convention. Emmanuel Tia Nabila, the organization’s food security program coordinator, said that the development process begins with a meeting between ADDRO staff and the leaders of a community with the in-kind resources—land, crops, labor and farming experience—required for success. “We profile the community’s production potential and challenges, and what interventions can result in higher yields,” he said.

An entire community can benefit from ADDRO’s partnership if about twenty farmers are committed to planting crops and coming to meetings, said Nabila. Both female and male farmers are recruited. “Crop production and cooking is traditionally women’s work,” he said. “But with higher education, men [realize that they should] learn farming.” ADDRO makes it easier for women to own land and encourages them to cultivate their own crops. When the organization provides seeds, donkeys and plows to farming families, it does so in ways that give women a say in management and control. “This prevents women’s fields from sitting until men are done with the equipment,” said Ayeebo.

A farmer who participates in ADDRO’s food security program

Juliana Awini, project officer at ADDRO, said that once a community is chosen to participate in a farming program, ADDRO begins by holding an education seminar at which an agricultural expert teaches new planting and cultivation methods. Then, when the rains come, ADDRO provides participating farmers with seeds and fertilizer. Farmers have the benefit of seeing prospective results in advance, as ADDRO’s demonstration farm measures the results of traditional farming practices against the improved management it promotes in its program. Participants in ADDRO’s program also have the benefit of using community mills and processing equipment to process their crops, and they can receive assistance navigating the network of crop assemblers, processors and market vendors required to get crops to consumers.

ADDRO, whose largest funder is Episcopal Relief & Development, also runs programs that address integrated healthcare, rehabilitation of people with physical disabilities and blindness, gender awareness, disaster relief, and water and sanitation. ADDRO’s work funded by the popular NetsforLife® campaign has not only reduced malaria in participating villages but also built the development organization’s capacity for community-based work to address HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and hepatitis B.

“The Gospel of Jesus is incomplete without addressing poverty, disease and injustice,” said Ayeebo. “ADDRO is the social wing of the diocese that completes the evangelistic mission of the church.”

Learn more about Episcopal Relief & Development’s work with ADDRO, and visit the House of Deputies Tumblr and Facebook page to see photos and find out more about the pilgrimage.