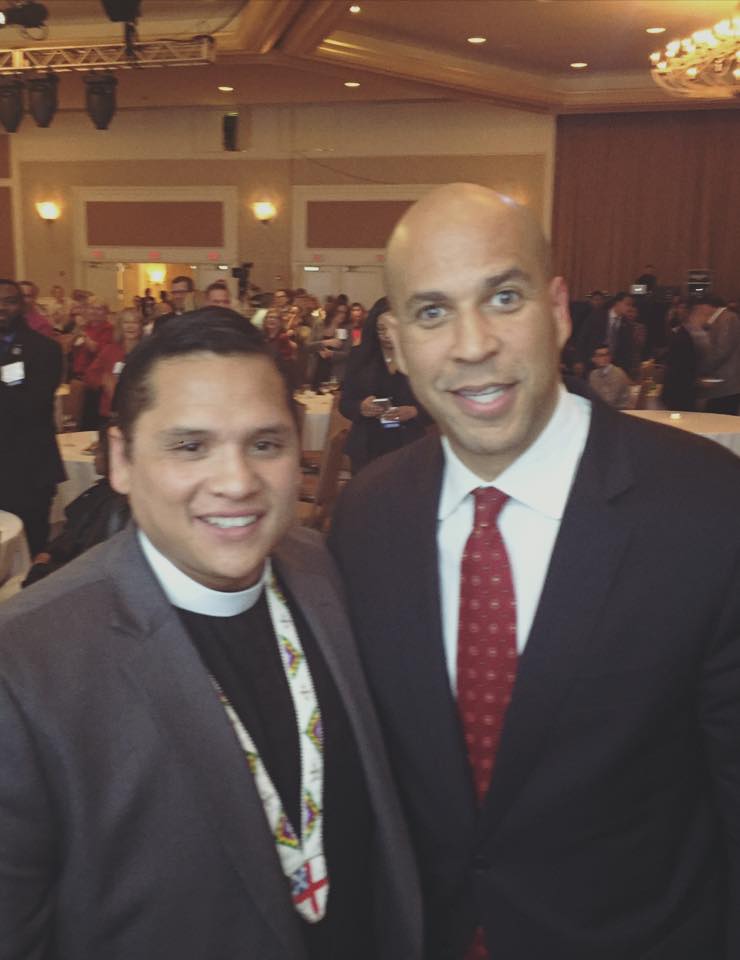

Mauai and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker at SIX

Deputy Brandon Mauai of North Dakota spent months helping to lead the Diocese of North Dakota’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline, but now that the immediate threat to water sources and sacred land on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation has lifted, he has a new mission.

“This is not just happening at Standing Rock,” he says. “It’s happening everywhere. Social injustice and environmental racism happened in Flint,” he says, referring to the contamination of public water with lead earlier this year, “and the same things are happening to Ojibwe people in Minnesota and in Navajoland, where another pipeline has been proposed.”

“We have to recognize the injustices and work toward reconciliation.”

On December 4, Mauai was on his way to Washington D.C. when the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it was denying an easement for the Dakota Access Pipeline to cross the Missouri River above the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. He was traveling to the capital to deliver a petition asking President Obama to stop the pipeline and call for an investigation of the military tactics used by local law enforcement against peaceful advocates at the pipeline site. A prayer vigil at St. John’s Episcopal Church on Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, was planned for that evening.

“We went to visit Senator Heidi Heitkamp’s office, where I spoke not only as an enrolled member of Standing Rock but as a clergy member of the Diocese of North Dakota and a leader of the Episcopal Church as a General Convention deputy,” he says. “We sat down with staff and talked about justice and the need for an investigation.” Jayce Hafner of the Episcopal Church’s Office of Government Relations arranged Mauai’s visits with legislators and accompanied him.

After a visit with Senator Al Franken’s staff, Mauai spoke about Standing Rock to a gathering of 400 state legislators hosted by State Innovation Exchange (SIX). He shared the stage with Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, from Flint, Michigan, and emphasized to the lawmakers that they bear responsibility “to speak for people who can’t speak.”

Mauai gives an interview to PBS’s Religion & Ethics Newsweekly

The church has the same responsibility, Mauai says. “For years the church has had a history with native people. There has been this ongoing process of reconciliation–we’ve always talked about apologizing and trying to reconcile. But when the church is there and is a voice among the people, it starts the process of reconciling relationships between the church and people.”

The church needs to stand with disenfranchised people not just in native communities, he says, “but all communities where we are called to serve, whether it’s urban areas, reservations, or with the folks in poorer communities. That’s where we need to do a lot of our work.”

“This is what the Jesus Movement does,” he says. “We have such a rich history in the Episcopal Church. This Jesus Movement thing almost seems new, but it’s not. It’s asking us to be with people who can’t be heard.”